The word will get out somehow, so I'll declare it here. In the unscripted preface to a paper I just gave at Dartmouth, I confided to my audience that the reason I became a medievalist has much to do with my sixth grade reading of The Lord of the Rings. [Invoke every cliche you wish at this point.]

I also stated that, even though I enjoyed the filmed version, for me the most unfortunate omission was the encounter with the Barrow Wight, that undead creature who reminds me so much of the Norse draugr. That's the scene early on when Frodo finds himself inside an ancient grave, menaced by a cadaver he glimpses only as a disembodied hand ... and learns that the world into which he has been thrown is at once darker and fuller than he could ever have imagined. Since I read that scene as a boy, barrows have had an eery grip on my imagination -- probably because Tolkien is so adept at evoking the lethally uncanny there. I also appreciate the obscured glimpse the barrow scene provides of histories that have unfolded beyond the scope of the already capacious Big Mythology of the Lord of the Rings cycle.

And that childhood reading is why I happened to be pontificating about fairy mounds, alternative worlds, and lost British history in Hanover NH last Thursday.

Saturday, April 29, 2006

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

Fairy Mounds and British Literature

I'm on my way to NH to present a paper . Here is the opening, on hills as portals to other worlds and on feasts refused.

----------

Medieval Welsh and Irish texts offer stories of worlds that exist in strange contiguity to everyday life. The Welsh otherworld of Annwn finds its gateway at Gorsedd Arberth, a mound atop which adventurers like Pwyll sit to seek wonders. In the Irish story of Cu Chulainn's love for Fand, queen of the sidhe, the hero enters a parallel "fairy" universe through a nondescript mound of earth. The Wasting Sickness of Cu Chulainn and the Only Jealousy of Emer [Serglige Con Culainn ocus Oenet Emire] describes the beings who inhabit this subterranean world as not merely human, differing in their customs, ancient history, potency in magic. Cu Chulainn is "cured" of his self-destructive love for this Fairy Queen only through the intervention of an oblivion spell: he must forget the riches of her world in order to better inhabit his own. Like many Irish and some Welsh narratives involving mounds as portals to fay or demonic realms, The Wasting Sickness of Cu Chulainn seems to carry with it an untold story about the belatedness of a people to the land they now possess, figuring the territory's earlier inhabitants as an inhuman race whose traces are dwindling, whose presence lingers as if at a dimming twilight.

An eerily similar mound was transported into Yorkshire late in the twelfth century. The historian William of Newburgh described how as a drunken reveler stumbled homeward one night he heard singing resound from a tumulus (History of English Affairs 1.28). William assures us that this hill is quite near his own birthplace, and that he has seen it numerous times. On this particular night a door has opened in the mound to reveal a feast in progress. The celebrants invite the man to join them and even offer him a beverage. Not the most polite guest, he pours the drink from its ornate cup and flees on horseback to his village. In time the splendid goblet is passed to King Henry, and then circulates among the royalty as a curiosity. The object is thereby transformed from the key to another world to a deracinated souvenir of some vaguely exotic elsewhere. The feast once refused recedes from memory, taking with it the history of that community glimpsed in their conviviality.

What would happen, though, if the English drunkard had joined the celebration rather than stolen its tableware? What would happen if he had entered into conversation to its participants, if one of them had spoken the tale of who they were and what they honored at their table? Whose history would this creature narrate?

My guess is that this other story, barely glimpsed by an ordinary English man and narrated as a wondrous fragment by William of Newburgh, would be very different from the history that William composes, a history that can discern in this fairy mound not far from the place of his birth a lost tale rather than a living one. Were the celebrants of the subterranean repast invited to speak, the narrative they would tell would likely reveal the difference between English literature and British literature.

(with thanks to JKW for help with the Welsh)

Monday, April 24, 2006

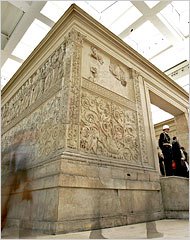

Augustan Age returns

The New York Times article on the controversy surrounding the exhibition of the Ara Pacis reminds me that I have something to be relieved about.

Every year the 3rd grade at Kid #1's school does a Wax Museum. This does NOT mean, like in that old Vincent Price horror film, children are dipped in hot wax. Students dress in period costumes and, when visitors press a button next to them, they recite the biography of the figure they are impersonating.

It was a foregone conclusion that Kid #1 would be a Roman emperor. Imagine my joy when he announced that he was not going to be Nero or Caligula (as I would have guessed) but Caesar Augustus. I asked him if that meant he was hoping for eventual deification as well; he remains undecided on that subject.

Now if only his father could get over his obsession with all that is unsavory about the Middle Ages.

Saturday, April 22, 2006

Malaysian Bigfoot speaks, declaring "Woooooo!"

From the BBC, courtesy of JKW:

The village of Mawai Lama in the Malaysian state of Johor is a sleepy row of wooden fronted shop-houses set back from the Sedili River.

Yet Mawai is one of the most intriguing places in Malaysia.

According to local historians, Mawai's original name was Mawas, and Mawas is the name locals give to a legendary creature known the world over as Bigfoot.

The people of Mawas certainly seem to believe in the creature from which their village takes its name.Some, like Aji the boatman, say they have seen it.

"It was about 10 or 11 at night. I saw something, but I didn't know what sort of creature it was. But I can definitely see the eyes were red. And it made a noise, Woooooo!" Aji said.

"Maybe it was scared off by my headlight and I was scared by him so we both rushed off in different directions and later I came back and found the footprints," he said.

The prints (image above) may have been made by Bigfoot. Then again, they also may have been made by an escaped clown.

Friday, April 21, 2006

Was Margery Kempe Jewish?

Here is a section from a paper I gave a while ago to the Medieval Club of New York. It's based on the Kempe chapter in my book Medieval Identity Machines, but tries to do a bit more with "Jewish" as a possible performative (and challenging) category in late medieval England.

---------------

Margery Kempe was obviously not Jewish. She was baptized a Christian and remained one faithfully throughout her life. Yet I wonder if Margery Kempe isn't Jew-ish. Kempe escaped constriction, escaped every identity that was thrust upon her. Her line of flight was composed of pure sonority, and by that I mean an escape from linguistic signification, from the prison of words tied to specific and inalterable meanings. I call this process the becoming-liquid of Margery Kempe, her self-dissolution into an embrace of sound, a flow of tears. This eruptive voice is connected to Kempe's obsession with storms. It is not only that her thunderous screams signify through sound but not meaning, just like Hebrew to the Christian ear (or eye, in manuscript illustration), but that her exorbitant mode of being allies her with the Jew as represented in early fifteenth century England. Energetically anti-Semitic, Margery Kempe in some ways deeply resembled that which she despised.

I begin with a scene from a drama that Margery Kempe may have witnessed in 1413, the year we encounter she and John on their home way from York drinking beer and posing hypothetical questions about their marriage (her husband asks "Would you have sex with me if a man threatened to decapitate me?" She, of course, answers that she would not.) When in the course of the York Cycle of Mystery Plays "The Death of Christ" is staged, the audience witnesses a Christian performing the role of a crucified Jew who speaks for the only time in his life Hebrew -- or, rather, a mixture of Hebrew and English:

Eli, Eli!

My God, my God full free,

Lama sabacthani?

Whereto forsook thou me?

These dying words are taken from Matthew's gospel, which in the Vulgate likewise quotes and translates the Hebrew [Mark has it in Aramaic]. I'd like to begin by asking what this Jewish Hebrew sounded like to the Christian audience that heard it. Was the immediate gloss understood? How many auditors were like Caiaphus, who in the play cannot comprehend what these alien sounds signify, but realizes their power? Ruth Mellinkoff has detailed the centrality of untranslatable Hebrew (the letters of which were often represented pictorially by "Hebrew"-style nonsense) to Christian fantasies of Jewish identity (Outcasts : Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages ). Kempe is a figure who likewise found herself labeled an outsider because of the alien sounds which issued from her mouth, someone who could not (like the Christ of the York mystery play) assimilate herself into Latin discourse (his last words are not Hebrew or English but simply in manus tuas ).

As Carolyn Dinshaw has so persuasively argued, Margery Kempe is queer, with all the suggestions of perturbing sexual alterity which cling to that term. The adjective "queer," moreover, fits Kempe's "wondirful," astonishing, unnatural voice better than her body, for it likewise "knocks signifiers loose," touches bodies, "making them strange." Eve Sedgwick answers the question "What's queer?" by comparing institutionalized heterosexuality to Christmas. Both "events," it should be noted, leave someone out: the queer, the Jew. These two familiar strangers have often been conflated, perhaps because they stand in extimate relation to the dominant. Both are disruptive, perhaps intolerable Others integral to the construction of homogeneity within the community which excludes them. Could Kempe's queer voice also be called Jewish?

Kempe is clearly not a Jew. Her devotion to Christ's passion is proof enough of her Christian orthodoxy. The Jewish population of her native Lynn had been exterminated in 1190, when a riot against them ended in massacre and conflagration. If any individual Jews returned thereafter, they were expelled from England a century before Kempe was born. She does, however, frequently speak of Jews. She codes condemning voices as Jewish, a semiotic maneuver that allows her the historical position of the persecuted Jesus (44). Her frequent prayers are directed toward the conversion of "Jewys, Sarazinys, and alle fals heretikys" (57), expressing the Christian desire for a universality that would do away with the "errant" differences of Judaism, Islam, and nondominant Christianities. Her vision of the Passion includes Jews who treat Jesus "so fowle and so ven[ym]owslych" that she weeps (79). Jews even replace Romans at the crucifixion, rending his garments and nailing Christ's body to the cross.

The adjectives "cruel" and "cursyd" are the most frequent modifiers of the noun "Jewys" in Kempe's Book. During her vision of the crucifixion, for example, both the Virgin and Kempe curse the Jews for their wickedness with just those adjectives. When the Jews reply to the grieving Mary, their voices are described by a familiar adverb: "And than hir thowt the Jewys spokyn ageyn boystowsly to owr Lady and put hir away fro hir sone" (80). When the Jews answer back, their voice echoes "boystowsly," without reported verbal content; their voice, rather than their hands, seems to be the force which moves Mary from her dying son. "Boystows" is, of course, the very adjective which Kempe deploys repeatedly to describe her own voice as a disruptive, astounding sonic flow capable of moving bodies and perturbing communities. Could Kempe's voice be "boystows" in the same way as that the voice of the Jews is "boystows"? The thunderstorms with which Kempe forms her sonorous alliance suggest this possibility, bearing with them as they do suggestions of the biblical voice of thunder which echoes throughout the books of Exodus and Job as the God of the Jews speaks to his chosen people; the God of the Christian bible never speaks in thunder.* Oddly enough, Kempe is even accused of being a Jew at one particularly fraught moment in the text. In the city of York, a place where she has experienced "gret wepyng, boistows sobbyng, and lowde crying" (51), Kempe is asked during the archbishop's interrogation "whedyr sche wer a Cristen woman er a Jewe?" (52). Used loosely, "Jewe" of course means something like "heretic." Yet at the same time, underneath its metaphorization, "Jewe" always also uniquely signifies a racialized, traumatic body for English Christendom, and empty and excluded place around which Englishness itself perhaps formed.

Kempe's exorbitant voice structurally places her not only in a queer relation to dominant meanings and institutions, but also in a disjunctive position similar to (though certainly not identical with) the inassimilable Jew: an intractable outsider in the midst of medieval community, an inexcluded Other whose recalcitrant, "untranslatable" Hebrew likewise figures the limits of linguistic universality and limns the Christian possible. Sylvia Tomasch has argued that the Jew was "central not only to medieval English Christian devotion but to the construction of Englishness itself," especially after the Expulsion. If Englishness is catalyzed around an empty space, that of the absent Jew, then any identity challenging to this new cohesiveness risks become Jew-ish, Jew-like.

Yet unlike this "virtual" or "spectral" Jew who figures so prominently in Kempe's own rhetorical construction of Christianity, Kempe attains for her voice both authority and power, at least for a brief period in the fifteenth century, and for the past few decades of our own era. Through the force of her "boystows" flow of tears and cries, Kempe moves into the position of the sexual, social Other, but in precipitating new kinds of community refuses the possibility – the thinkability -- of an identity-sustaining alliance with those racial, religious Others with whom she is already queerly close. Kempe does not recognize the Jewish timbre of her voice. By closing off further irruptions of alterity, Kempe constricts her Christian selfhood and leaves unquestioned the place of the Jew within it.

That Kempe's experiments in identity could disrupt sexual and social borders but stop at the barrier of race is not surprising. Medieval Christian identity was sustained by elaborate, seemingly intractable racial fantasies centered upon the supposed absolute otherness of Jews and Saracens. Margery Kempe did not recognize the voice of the racial other echoing within her own, but that does not mean that she could not.

---

*Kempe's anxious obsession with thunderstorms is displayed throughout her book, often linked to worries over and triumphs of her own voice and authority. It is surprising that more people haven't remarked on it.

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Love cows?

It is probably inappropriate to post on this, but then again I can invoke my fantastic Medievalist Powers of Historicization to give it a scholarly patina and render it OK.

When not translating obscure Latin passages or eating lunch, one of the things I've been devoting my sabbatical time to is helping to organize a carnival, a fundraiser for the public school that Kid #1 attends. I'm in charge of the Young Kids Games. In honor of the carnival's rodeo theme, one of the feats of skill I'm trying to put together for the tykes is a lasso challenge. So far I have a wooden rocking horse and a large plastic cactus ready to be looped by eager cowpokes. I was hoping to track down an inflatable cow to add to the game (medievalists love triads). A froogle search for "inflatable cow" brought up the following: Elsie the Mooing Cow, promised to be "udderly hilarious." Looks promising, I thought, as long as it is tall enough for the kids to rope. Cute little smile, black and white polka dots, makes a moo sound .... good, good, good.

When I noticed the line in the product description that Elsie "includes rear entry opening," though, my chaste little brain hesitated (for what? realism? did a farmer design it?). Then when I saw that Elsie "includes samples of spanish fly and lube" I realized that maybe -- just maybe -- she wasn't quite the bovine we want the little ones to play with at Young Kids Games.

So how does this relate to the Middle Ages? Read your Gerald of Wales! He condemned the Irish for their interspecies ardor, and specifically for their inordinate love of cattle (more on this here). What Gerald would make of human relations with plastic inflatable cow substitutes, I wouldn't venture to say.

When not translating obscure Latin passages or eating lunch, one of the things I've been devoting my sabbatical time to is helping to organize a carnival, a fundraiser for the public school that Kid #1 attends. I'm in charge of the Young Kids Games. In honor of the carnival's rodeo theme, one of the feats of skill I'm trying to put together for the tykes is a lasso challenge. So far I have a wooden rocking horse and a large plastic cactus ready to be looped by eager cowpokes. I was hoping to track down an inflatable cow to add to the game (medievalists love triads). A froogle search for "inflatable cow" brought up the following: Elsie the Mooing Cow, promised to be "udderly hilarious." Looks promising, I thought, as long as it is tall enough for the kids to rope. Cute little smile, black and white polka dots, makes a moo sound .... good, good, good.

When I noticed the line in the product description that Elsie "includes rear entry opening," though, my chaste little brain hesitated (for what? realism? did a farmer design it?). Then when I saw that Elsie "includes samples of spanish fly and lube" I realized that maybe -- just maybe -- she wasn't quite the bovine we want the little ones to play with at Young Kids Games.

So how does this relate to the Middle Ages? Read your Gerald of Wales! He condemned the Irish for their interspecies ardor, and specifically for their inordinate love of cattle (more on this here). What Gerald would make of human relations with plastic inflatable cow substitutes, I wouldn't venture to say.

The Green Children, Broadway version

Remember the Green Children?

The poet Glyn Maxwell has written a play about them. Here's an excerpt from a review in today's New York Times:

Set in 12th-century England during a civil war never precisely explained, "Wolfpit" tells the fantastic, quasi-historical story of two children, colored green from head to foot, who suddenly appeared in a field at harvest time, dressed in garments of unfamiliar material and speaking an unknown tongue. The boy, who refused food other than green beans, retained his skin color and died, while the girl accepted other food, turned "sanguine" and became an object of avid male attention. The plot's chief concern is how this disturbance lays bare the surrounding characters' hypocrisy, selfishness, greed and general turpitude.

The reviewer, Jonathan Kalb, praises the "eloquent awkwardness" of Maxwell's pentameters, calling his text "refreshingly strange." Seems appropriate.

The play has a flash-heavy website, wolfpit.org

Monday, April 17, 2006

The archipelago of England

The title of this blog entry is the working title for my next research project: an examination of how medieval England was haunted by the multicultural, polyglot archipelago from which it emerged -- a British Isles that England supposedly superceded and assimilated. I'm interested in how "England" began to pass itself off as a synonym for "Britain," and what this substitution-which-is-not-an-equivalence ineptly obscured.

I'm teaching a graduate seminar on the topic next autumn. The list of primary works looks something like this:

Bede, Life of St Cuthbert

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville

The Life of Saint Columba

Marie de France, Lais

Orkneyinga Saga

Asser's Life of King Alfred

Julius Caesar, The Conquest of Gaul

Gerald of Wales, Journey Through Wales

Middle English Breton Lays

Nennius

Morte Arthure

Wace and Layamon

The Mabinogion

Chaucer, "Wife of Bath's Tale" "Franklin's Tale"

That's quite a bit, and probably needs to be pared, considering I hope we'll do a fair amount of reading in secondary sources (especially postcolonial-inflected medieval studies, but also in history and theory more generally). I place it here, though, because I'm interested in hearing other people's thoughts on what such a course might include -- primary texts and criticism both.

Friday, April 14, 2006

Guthlac, Mercia, and Anglo-Saxon Colonialism

Here, in response to the discussion in the "Fantasies of the Aboriginal" post, is an excerpt from Medieval Identity Machines on the Anglo-Saxon saint Guthlac and the subjugation of the Britons. It's taken from a chapter ("The Solitude of Guthlac") on the legends as Mercian literature in which the saint's celibate body becomes a figure for the emergent kingdom itself. In the book I then try to read the Guthlac stories against the saint and with the demons, arguing that the model of identity at work between holy man and monsters is a dispersive one.

(The above image depicts Guthlac departing from the warband he once commanded. Inspired by heroic legend, Guthlac had attempted in his youth to become another Beowulf, but he eventually left that martial world behind to become a swamp-dwelling hermit. The picture above is much later, c.1210, but suggests how alluring the story was for centuries thereafter. It's from the Harley Roll Y. 6 and can be found here)

------------------------

Writing in 1868, Charles Kingsley envisioned in the Anglo-Saxon saint Guthlac a progenitor of the "fenmen sailing from Boston deeps" who "colonized and Christianized [the New World] 800 years after St. Guthlac's death." Just as the crowning achievement of the saint's descendants in England was, according to Kingsley, the founding of Cambridge University, their latter day feat of heroism was the erection of Harvard University on converted barbarian shores (The Hermits 308-12).

Kingsley's colonialist fantasy of continuity between the settling of the Fenlands and the colonization of North America is in some ways a logical extension of the medieval trajectory of the Guthlac legends. The demons detest this saint, after all, not for his holiness but because he has seized their dwelling place, their long-held territory (Guthlac A 205-13). Both Felix's Vita Guthlaci [the earliest account of the saint's life, written in Latin] and the Old English poem Guthlac A are texts obsessed by the annexation of new land and its conversion into secure possession. Laurence K. Shook argued in 1960 that the hill in the fens for which Guthlac battles its resident demons represents "all that is significant in the spiritual life of the good Christian … [The poet's] use of the barrow removes it from the category of a mere geographical appendage to a religious theme." Like the formalistic analysis to which Guthlac A has been frequently subjected, theological interpretation like this has its value, but (as Karl P. Wentersdorf has observed) the poem "is more than an Anglo-Saxon Pilgrim's Progress." Despite its potential abstraction into universalizing Christian allegory, the fenland promontory which Guthlac settles also remains a "geographical appendage" which is marked -- like Guthlac himself -- by a particularly Mercian history. Guthlac's settlement of the hill is described by the old english poem in deliberately multivalent terms:

The undiscovered place stood known to the Lord, [but] empty and uninhabited, far from ancestral domain [ethelriehte ], awaited the claim of better guardians. (215-17)

In language of impending, fortunate discovery and subsequent legal possession, the passage envisions a promised land that lies fallow (idel), awaiting new masters to transform its empty wildness into inheritable domain (ethelriehte ["ancestral land"] is used in the Old English translation of Exodus to describe the Promised Land).

Guthlac's struggles unfold in the Fenlands, the vast expanse of peat, silt, uplands, and islands which formed a crescent of wilderness around the Wash. Guthlac's colonization of the demon's cherished home (the tumulus or beorg specifically, but the Fens more generally) reenacts in miniature the dispossession of that very territory by the numerous Northern peoples who, beginning in the fifth century, sailed to Britain and remained in the region. Bordering important Mercian settlements, the fens had been occupied centuries before the arrival of the northerners by Celtic peoples, many of whom had ancient histories of resistance against attempts at displacement. About a hundred miles from Crowland, for example, an area not far from Norwich had been christened by the invading Romans Venta Icenorum, "marketplace of the Iceni." As is the case with all too many of the British peoples whose names are mentioned (and Latinized) by Caesar and Tacitus, very little is known about them, but famously among their number was Boudica (Boadicea), the rebel queen who led a Celtic alliance against the Roman annexation of Britain, reducing the colonia of Colchester and the trading town of London to ashes.

Romans and Romanized Celts had successfully settled much of the fens, draining marshy expanses for agriculture, industry, and habitation. With the withdrawal of the Roman legions, however, the area became once again swampy and sparsely inhabited. In the Fenlands of the eighth century, the kingdom of East Anglia rubbed against Mercia and formed a borderland which may have harbored an as yet unassimilated British population. Yet even if the entire population of native Britons had been displaced or (more likely) absorbed into "Anglo-Saxon" polities long before Guthlac's arrival, his battles against the demons enacts in the Fens a struggle taking place on the other side of the kingdom of Mercia, a martial engagement in which he himself had been involved as a young warrior.

The eighth century Mercian hegemony was marked by its great battles over land, with Mercia finding the limits of its westward push at that border where Offa erected his dyke. Felix clearly had the ongoing wars against the Britons in mind as he composed the Vita Guthlaci. In describing the Brittones as "the implacable enemies of the Saxon race [infesti hostes Saxonici generis], troubling the nation of the English [Anglorum gentem] with their attacks, their pillaging and their devastations of the people" (XXXIV), Felix was able to construct a flattened, pan-racial "Anglo-Saxon" identity for the island (Saxonici and Anglorum appear to be synonyms here). In providing a common enemy, that is, Felix's Britons also construct a shared sense of "English" race subsumable under the Mercian body of Guthlac, who at first as warrior and later as saint battles this threat to the cohesion of gens, natio, theod.

In a particularly striking episode of what Alfred P. Smyth describes as ethnic hatred, just as the Welsh are invading Mercia from the west during the reign of King Coenred, a crowd (tumultuantis turbae) of demons impersonate a band of British marauders and set fire to Guthlac's dwelling, attacking him with spears. Guthlac chants a psalm and the demon-Britons vanish velut fumus, like smoke (XXXIV). Two points are central here. Language rather than dress or bodily appearance characterizes these Britons; Felix says that Guthlac knows these marauders by their "sibilant speech," and the Old English translation of the Vita sancti Guthlaci goes so far as to label the chapter Hu tha deofla on brytisc spræcon, "How the devils spoke in Brittonic." Second, Guthlac recognizes this linguistic difference immediately because it is also a part of him, the forced learning of a time spent in captivity among the Britons during his days as a warrior. That Mercia might ingest formerly British lands while their inhabitants simply vanish velut fumus would have been a powerful and attractive group fantasy. Yet Guthlac's implicit recognition is that brytisc is an unassimilated remainder within his "pure" body. An otherness which can return to haunt, it reminds of a history of violence, gestures toward troubling fragmentations and internal differences. Celtic-speaking peoples within and at the edge of Anglo-Saxon collectivity offered a pointed challenge to Mercia's imagining itself as a homogenous community, to declaring the island an unambiguous ethelrieht.

Like the Briton episode from the Vita Guthlaci, Guthlac A is suffused with colonial desires, displacing into religious history a version of the engagement which was then occurring as martial history. The vastness of the fen was once wholly occupied by the demons (143-44), and the mound upon which the saint settles may, as in Felix's account, be a topography marked by multiple colonizations. After Guthlac removes the demons from their last remaining dwelling, the land belongs to Mercia. His settlement enacts a fantasy of manifest destiny, displacing the ethnic violence at Mercia's border to an internal space where a triumph can be spectacularly staged over external and internal difference simultaneously. Representing the Britons as banished demons and Guthlac as a man singularly in possession of himself offers a culturally useful fantasy of a male body whose identity is uncomplex, internally imperturbable. Guthlac's stabilitas -- his immobile, granite-like, and unconflicted subjectivity -- embodies everything Anglo-Saxon England in general and eighth century Mercia in particular as potentially corporate identities were not.

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Ignoge's eyes

Following from yesterday's post, here is a medieval example of an unnarrated, barely glimpsed woman's story. It's taken from a section on Geoffrey of Monmouth in Hybridity, Identity and Monstrosity in Medieval Britain.

No woman's story in Geoffrey's text resonates more lastingly than that of Ignoge, the Greek princess forced to become bride to Brutus. Geoffrey of Monmouth ordinarily composes his narrative with sangfroid: little human feeling animates its accounts of battles, wonders, political intrigue, strife. He is not given to moments of aching identification such as William of Malmesbury's wrenching account of the sinking of the White Ship (History of the English Kings 5.419). Ignoge has little presence in Geoffrey's text, but as she sets sail with a husband she never chose for a future that is wholly uncertain, we are given a lingering depiction of her last vision of her native land. The episode is at once so evocative and so moving that, as Robert Hanning observes, it "interrupts the flow" of the narrative, so that "for a moment the issues of national birth and freedom are forgotten; history itself is forgotten." Here is Geoffrey's vivid portrayal of the fading shores of home as glimpsed through bereft Ignoge's eyes:

As Ignoge's home slowly recedes, lost are the possibilities for any life she might have desired for herself, for any history she might have dreamed. Destined to become an appendage of Brutus, the source of his progeny, we next see Ignoge in what appears to be an afterthought, legitimating the birth of three sons (2.1). She is not mentioned again. Her children divide the land and carry on their father's work. It never occurs to them that in their bodies the blood of Troy mingles with that of Greece, that they possess hybrid blood in which two enemies have uneasily been conjoined. The sons of Brutus assume that they are simply Britons, as their father christened his people. They never dwell upon the complexities of history and descent.

Ignoge's gaze opens up the possibility of another story. An alien among strangers, suspended between cultures and no longer able to be of one or the other, Ignoge embodies everything her children so easily forget. Yearning for a home that can never be hers, this princess conveyed to an unfamiliar place suggests the difficulties faced by those who carry an identity full of difference, ambivalence, conflict. Ignoge inhabits that middle space where conqueror meets conquered, where a war unfolds between loathing and desire. She looks back to a receding homeland and forward to the impossible bind of mixed progeny on an island increasingly dominated by a single people. Ignoge is Greek, her husband Trojan, her children Britons, but her tears prevent such easy separations.

Geoffrey of Monmouth dreamed of a world where at first glance history and descent keep insular peoples solitary. As his textual world unfolds in all its intricacy, however, the peoples that populate Britain mingle and become -- despite their own fervent belief to the contrary -- impure. Geoffrey's ambivalent entwining of purity with hybridity is rather like William of Malmesbury's. Both writers posited clean separations but undercut them with anxious, medial spaces: one through marvels, the other through blood. The separateness of the island's peoples might be an impossible dream, but that did not stop this dream from being passionately embraced, much to the sorrow of those who carried blood that could never seem untainted. For these impure beings history was filled with heartache, and the present never ceased to hurt.

No woman's story in Geoffrey's text resonates more lastingly than that of Ignoge, the Greek princess forced to become bride to Brutus. Geoffrey of Monmouth ordinarily composes his narrative with sangfroid: little human feeling animates its accounts of battles, wonders, political intrigue, strife. He is not given to moments of aching identification such as William of Malmesbury's wrenching account of the sinking of the White Ship (History of the English Kings 5.419). Ignoge has little presence in Geoffrey's text, but as she sets sail with a husband she never chose for a future that is wholly uncertain, we are given a lingering depiction of her last vision of her native land. The episode is at once so evocative and so moving that, as Robert Hanning observes, it "interrupts the flow" of the narrative, so that "for a moment the issues of national birth and freedom are forgotten; history itself is forgotten." Here is Geoffrey's vivid portrayal of the fading shores of home as glimpsed through bereft Ignoge's eyes:

The Trojans sailed away ... Ignoge stood on the high poop and from time to time fell fainting in the arms of Brutus. She wept and sobbed at being forced to leave her relations and her homeland; and as long as the shore lay there before her eyes, she would not turn her gaze away from it. Brutus soothed and caressed her, putting his arms round her and kissing her gently. He did not cease his efforts until, worn out with crying, she fell asleep (1.11)

As Ignoge's home slowly recedes, lost are the possibilities for any life she might have desired for herself, for any history she might have dreamed. Destined to become an appendage of Brutus, the source of his progeny, we next see Ignoge in what appears to be an afterthought, legitimating the birth of three sons (2.1). She is not mentioned again. Her children divide the land and carry on their father's work. It never occurs to them that in their bodies the blood of Troy mingles with that of Greece, that they possess hybrid blood in which two enemies have uneasily been conjoined. The sons of Brutus assume that they are simply Britons, as their father christened his people. They never dwell upon the complexities of history and descent.

Ignoge's gaze opens up the possibility of another story. An alien among strangers, suspended between cultures and no longer able to be of one or the other, Ignoge embodies everything her children so easily forget. Yearning for a home that can never be hers, this princess conveyed to an unfamiliar place suggests the difficulties faced by those who carry an identity full of difference, ambivalence, conflict. Ignoge inhabits that middle space where conqueror meets conquered, where a war unfolds between loathing and desire. She looks back to a receding homeland and forward to the impossible bind of mixed progeny on an island increasingly dominated by a single people. Ignoge is Greek, her husband Trojan, her children Britons, but her tears prevent such easy separations.

Geoffrey of Monmouth dreamed of a world where at first glance history and descent keep insular peoples solitary. As his textual world unfolds in all its intricacy, however, the peoples that populate Britain mingle and become -- despite their own fervent belief to the contrary -- impure. Geoffrey's ambivalent entwining of purity with hybridity is rather like William of Malmesbury's. Both writers posited clean separations but undercut them with anxious, medial spaces: one through marvels, the other through blood. The separateness of the island's peoples might be an impossible dream, but that did not stop this dream from being passionately embraced, much to the sorrow of those who carried blood that could never seem untainted. For these impure beings history was filled with heartache, and the present never ceased to hurt.

Wednesday, April 12, 2006

Zipporah's story

The seder plate is ready to be loaded with its Very Symbolic Items. Our copy of My Favorite Family Haggadah is good to go. Elijah's cup awaits its wine. We even have our bag of plagues to liven up Pesach (Favorite plague from this bag: the "cattle plague," a plastic cow with eyes that ooze when you squeeze it).

Now that Kid #2 is two years old, she will be able to engage in the seder in a way that she couldn't previously: in past years her participation was mainly limited to spitting matzoh out of her mouth and vocalizing loudly when the food took too long. I've been thinking a lot about rituals that will acknowledge a little better the presence -- and importance -- of this little girl. Miriam's cup, I know, is often used alongside Elijah's goblet to honor the role of a women not only in the biblical story but in Jewish history more generally. Miriam is an attractive figure for inclusion, too, because she is one of the few women in the bible who is not most noteworthy for her role as wife, lover, or mother: she is the sister of Moses, the architect of his survival, a jubilant musician, a leader of women in song, dance, and prayer.

We will have Miriam's cup on our table tonight. But I've also been contemplating a way to honor a woman from the Moses story who has faded -- almost -- to oblivion. Zipporah the Midianite was the wife of Moses and the mother of his two sons. Though descended from Abraham, the Midianites were frequent enemies of the Jews, even the objects of genocide; they were supposed to be polytheistic as well. In the Middle Ages Zipporah was often held to be an Ethiopian (or Cushite; it's a legend based on an obscure biblical passage, and sometimes this dark-skinned spouse was thought to be the second wife of Moses). A non-Jew, perhaps a nonbeliever, annexed to a narrative that is not her own, Zipporah seems to me like so many of the women we medievalists know well from our reading: women who ubdoubtedly possessed rich histories and vibrant lives, but who now survive as a tantalizing fragment of stories untold.

As a figure for all those whose lives pass unrecorded Zipporah deserves remembrance.

Monday, April 10, 2006

anthropodermic bibliopegy

Police plea on macabre book find

Police are trying to locate the owner of a 300-year-old ledger, bound in human skin, found in a Leeds road.

Written mainly in French, its macabre covering was said to be a regular sight during the French Revolution. In the 18th and 19th Centuries it was common to bind accounts of murder trials in the killer's skin - known as anthropodermic bibliopegy.

The book was discovered in The Headrow and may have been discarded after a burglary, detectives said.

-- from the BBC

I knew there was some dark undercurrent to the annual International Medieval Congress in Leeds. Now we catch a glimpse of just how necromatic it might actually be.

Fantasies of the Aboriginal

Here is that syllabus I promised for a graduate seminar I taught last autumn. My current research project pulls from these materials, so any comments and bibliography are most welcome.

ENGLISH 205: FANTASIES OF THE ABORIGINAL

This course will examine how "deep time" and the prehistoric have been narrativized by those who have little access to such lost times and places. The materials examined will be mostly medieval, and include texts like Beowulf, some saints' lives, Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (the text that "invented' King Arthur) and its translations. Some texts, though, will feature dinosaurs and other creatures from more modern Lost Worlds. Much of our time will be spent exploring how anterior peoples (aboriginal or not) who occupy colonized land are represented, and what kinds of stories they are allowed. Contemporary postcolonial theory and theorizations of First Nations, nativism, and the indigenous will form our secondary readings. We will also look closely at the life of objects like Stonehenge that, once the stories of people who created them become inaccessible, develop fantasy histories that reimagine the past. Finally, we will keep circling back to how stories of the distant past are always stories of the present, whether these narratives are medieval or modern.

SCHEDULE OF READINGS

An asterisk indicates the book is on reserve at the Gelman library. Copies of essays not at the library can be found in the folder on my office door. Remove only to xerox.

Sept. 6 Comparative Prehistories

- Chris Gosden, Prehistory: A Very Short Introduction

For Further Reading - Martin J. S. Rudwick, Scenes from Deep Time: Early Pictorial Representations of the Prehistoric World (University of Chicago Press, 1995)

- Henry Gee, In Search of Deep Time: Beyond the Fossil Record to a New History of Life (Free Press, 1999)

- Paul Semonin, American Monster: How the Nation's First Prehistoric Creature Became a Symbol of National Identity (New York University Press, 2000)

- Peter D. Ward, Gorgon: Paleontology, Obsession, and the Greatest Catastrophe in Earth's History (Viking 2004)

Sept. 13 The Writing of Stones

- *Aubrey Burl, Prehistoric Avebury Introduction, chapters 9 ("Purpose") and 10 ("Avebury after Avebury") [library reserve]

- Aubrey Burl, The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany chapters 4 ("Function: Calendars, Cults and Sex") and 18 ("Stonehenge") [folder]

- *Elizabeth Hill Boone and Walter D. Mignolo, eds. Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes "Introduction: Writing and Recording Knowledge" (Boone) and "Signs and Their Transmission: The Question of the Book in the New World" (Mignolo) [library reserve]

- Roger Caillois, The Writing of Stones (University Press of Virginia, 1985)

For Further Reading

Sept.20 In Principio: Contested Instigations

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People Book 1 & 2

- Gildas, On the Ruin of Britain [folder]

- Kathleen Biddick, The Shock of Medievalism, "Bede's Blush" [folder]

- Nicholas Howe, "From Bede's World to 'Bede's World'" [folder]

- *Nicholas Howe, "Anglo-Saxon England and the Postcolonial Void" in Postcolonial Approaches to the European Middle Ages, ed. Kabir and Williams [library reserve]

- Uppinder Mehan and David Townsend, "'Nation' and the Gaze of the Other in Eighth-Century Northumbria," Comparative Literature 53 (2001) 1-26

- Kathleen Davis, "Nation Writing in the Ninth Century: A Reminder for Postcolonial Thinking about the Nation." Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 28 (1998) 611-37

- "Special Issue: Gender and Empire," ed. Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing, Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 34 (2004), especially the introduction by Lees and Overing ("Signifying Gender and Empire"), Fred Orton "Northumbrian Identity," and Nicholas Howe, "Rome: Capital of Anglo-Saxon England"

- Walter Goffart, The Narrators of Barbarian History(A.D. 550-800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon (Princeton University Press, 1988).

- Sarah Foot, "The Making of Angelcynn: English Identity Before the Norman Conquest." Transactions of the Royal Historical Society,6th series 6 (1996) 25-49.

- Patrick Wormald, "Bede, the Bretwaldas and the Origin of the gens Anglorum." Ideal and Reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Society, ed. Patrick Wormald, Donald Bullough and Roger Collins (Oxford, 1983) 99-129.

For Further Reading

Sept. 27 Is the Subaltern Heard?

- Felix, Life of Saint Guthlac [folder]

- Gayatri Spivak, "Can the Subaltern Speak?" [folder]

- *Stephen Greenblatt, "Invisible Bullets" in Political Shakespeare, ed. Dollimore [library reserve]

- Ed White, "Invisible Tagkanysough" [PMLA 120.3 2005, folder]

- Elizabeth A. Povinelli, "The State of Shame: Australian Multiculturalism and the Crisis of Indigenous Citizenship," Critical Inquiry 24 [Winter 1998]: 575-610. See also the response by John Frow and Meaghan Morris in CI 25 [Spring 1999].

For Further Reading

Oct. 4 No Class (Rosh Hashanah)

Oct. 11 Instigating the English Canon

- Beowulf, trans. Seamus Heany (Norton edition)

Oct. 18 The Monster and the Aboriginal: Reading Grendel

- J. R. R. Tolkien, "The Monsters and the Critics"; Jane Chance, "The Problem of Grendel's Mother"; Roberta Frank, "The Beowulf Poet's Sense of History"; Fred C. Robinson, "The Tomb of Beowulf" (reprinted in back of Norton edition of the Heaney translation)

- Alfred Siewers, "Landscapes of Conversion: Guthlac's Mound and Grendel's Mere as Expressions of Anglo-Saxon Nation-Building" [folder]

- *Seth Lehrer, "'On fagne flor': The Postcolonial Beowulf, from Heorot to Heaney" in Postcolonial Approaches to the European Middle Ages, ed. Kabir and Williams [library reserve]

Oct. 25 Native Knowledges

Please visit the National Museum of the American Indian prior to attending this class

- Ganeth Obeyesekere, The Apotheosis of Captain Cook

- Marshall Sahlins, How 'Natives' Think

- W. Richard West, The Changing Presentation of the American Indian: Museums and Native Cultures (University of Washington Press, 2000)

For Further Reading

Nov. 1 Colonial Systems and Their Exteriors

- Gerald of Wales, The History and Topography of Ireland

- Patricia Ingham, Postcolonial Moves ed. Ingham and Warren, "Contrapuntal Histories" [folder]

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera [folder]

- Expugnatio Hibernica: The Conquest of Ireland, ed. and trans. A. B. Scott and F. X. Martin (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1978)

- Robert Bartlett, Gerald of Wales, 1146-1223 (Clarendon Press, 1982)

- James D. Cain, "Unnatural History: Gender and Geneaology in Gerald of Wales’s Topographia Hibernica," Essays in Medieval Studies 19 (2002) 29-43.

- Rhonda Knight, "Werewolves, Monsters, and Miracles: Representing Colonial Fantasies in Gerald of Wales's Topographia Hibernica." Studies in Iconography 22 (2001) 55-86.

- David Rollo, "Gerald of Wales' Topographia Hibernica: Sex and the Irish Nation." The Romanic Review 86.2 (1995) 169-90.

For Further Reading

Nov. 8 Counter-History

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, History of the Kings of Britain

Nov. 15 "The British"

- *Patricia Ingham, Sovereign Fantasies, "Introduction," "Arthurian Imagination and the 'Makyng' of History (chapter 1), "Arthurian Futurism and British Destiny" (chapter 2) [library reserve]

- *Michelle Warren, History on the Edge "Prologus historiarum Britanniae," "Arthurian Border Writing" (chapter 1), "Geoffrey of Monmouth's Colonial Itinerary" (chapter 2), "Resistance to the Past in Wales" (chapter 3) [library reserve]

- R. R. Davies, The First English Empire [folder]

- Lee Patterson, Negotiating the Past: The Historical Understanding of Medieval Literature (University of Wisconsin Press, 1987)

- John Gillingham, The English in the Twelfth-Century: Imperialism, National Identity and Political Values (Boydell Press, 2000).

- Geraldine Heng, Empire of Magic: Medieval Romance and the Politics of Cultural Fantasy (Columbia University Press, 2003)

- Postcolonial Moves: Medieval Through Modern, ed. Ingham and Warren (Palgrave Macmillan 2003)

- Kellie Robertson, "Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Translation of Insular Historiography." Arthuriana 8.4 (1998) 42-68

For Further Reading

Nov. 22 Translation, History and Loss

- Wace, Roman de Brut / A History of the British

- *Finke and Shichtman, King Arthur and the Myth of History chapter 1 ("'To Mend the Interrupted Sequence of Time'"), 3 ("Romance of Empire") and 4 ("Discontinuous Time") [library reserve]

Nov. 29 Hybrid Futures?

- Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture

- *Antonio Benitez-Rojo, The Repeating Island, "Introduction" and "From the plantation to the Plantation" (3-81) [library reserve]

Dec. 6 Paper Presentations

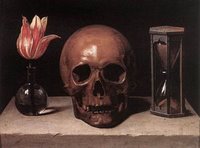

memento mori

A bittersweet meditation on moving into a deceased predecessor's office at Inside Higher Ed.

Because I am a medievalist and because death is such a vital (yes I mean to pun here; I think it is appropriate) part of medieval culture, there are times when -- as I sit in my office pondering some passage or other about worldly vanities and the transitoriness of life -- I contemplate my own end. What if I were to die suddenly and some faculty member who hadn't known me was charged with emptying out my desk, bookcases and files? Sadly, I believe that person would conclude (1) that I was inordinately fond of the world's ephemera (sitting on my windowsill right now are a plastic Shriner, a troll with orange hair, and a ceramic model of Fenway Park, among many other tchokes); and (2) that I have an unhealthy Post-It note fixation (I possess more than I could ever use, in various shapes and astounding colors). This new faculty member would then toss my back issues of Speculum into the trash, empty out my fire hazard collection of polyglot xeroxes ... and I would be gone.

Movies and the Middle Ages

A special cluster on Movie Medievalism from Exemplaria.

Favorite title: "Introduction: Getting Schmedieval."

Friday, April 07, 2006

And a souvenir just for this blog's readers

How could I go away and not bring you back a little something? Here is a shot of the overhyped but still strangely moving Hill of Tara, supposed to be the ancient throne of the Irish kings. Note the raindrops on camera lens: every now and then there is a sprinkle of precipitation in Ireland, I noticed.

Fun fact: the woman in the black coat slipped and fell into the mud as she attempted to scale the hill. We looked on in pity and mild amusement, but made no attempt to assist her.

Souvenirs of Ireland

The price any parent pays for travel is that the progeny will, upon your return, demand gifts. One of the many reasons I love having a nine year old boy is that anything I buy him, toy or book, will also be used by me.

My favorite finds for Kid #1 during my recent sojourn to Ireland are three books. Two are from the Horrible Histories series (see this post if you want to read about how the Horrible Histories nurtured his unhealthy interest in Caligula and Nero). The Cut-Throat Celts describes all kinds of gruesome activities among those "tribes" ("The Celts decapitated their victims. What did they do with all those heads?")... but my favorite part is the account of Irish saints. Sample:

Saint Brigit: Brigit's crosses are still set up on farmland in Ireland to protect crops and animals. This is because she used to punish people who stole her cattle by drowning or scalding them. She didn't have [Saint] Winifride's problem of princes chasing her because she made herself ugly by putting out one of her eyes. Horrible Joke: Why was Saint Brigit like a lonely teacher? Because she only had one pupil.The second book I brought home is from the same series, and provides a quick and snarky history of the city of Dublin. Sample paragraph:

Another horror story was that Dermot [MacMurrough, 1110-1171] gathered a pile of enemy heads after a battle and spotted the head of man he really hated. What did he do next?These are English books, and an American child would have to know some Britishisms (like the double meaning of cheek) to get all the jokes -- many of which involve hapless pensioners -- but the volumes are, all in all, great fun. And a kid could accidentally learn something along the way.

a) spewed

b) chewed

c) glued

Answer: Dermot sank his teeth into the face and tore at it. [This information is accompanied by an illustration of a severed head with bite marks in the appropriate place. A thought bubble coming from the head declares "He had a bit of cheek!"]

The third book I grabbed is children's science fiction, and utterly fascinating: Philip Reeve's Mortal Engines. Who wouldn't be entranced by a book that opens with the sentence ""It was a dark, blustery afternoon in spring, and the city of London was chasing a small mining town across the dried-out bed of the old North Sea"? I don't think I'm giving too much of the plot away in mentioning that London is a populous city creaking its way across an apocalyptic landscape, and that the mining town -- its hapless prey -- is toast.

And what did Kid #2 get? Not the Horrible Histories Toddler Edition (still waiting for that; I'd really like to know the nasty side of Thomas the Tank Engine), but a stuffed bear from Aillwee Cave, famous for its hibernation pits and bones of Ursos Arctos. [She cared nothing about where it was from, and simply calls the thing "Hugga Bear"].

via Savage Minds

The belief in the allegedly "Western" nature of democracy is often linked to the early practice of voting and elections in Greece, especially in Athens. Democracy involves more than balloting, but even in the history of voting there would be a classificatory arbitrariness in defining civilizations in largely racial terms. In this way of looking at civilizational categories, no great difficulty is seen in considering the descendants of, say, Goths and Visigoths as proper inheritors of the Greek tradition ("they are all Europeans," we are told). But there is reluctance in taking note of the Greek intellectual links with other civilizations to the east or south of Greece, despite the greater interest that the Greeks themselves showed in talking to Iranians, or Indians, or Egyptians (rather than in chatting up the Ostrogoths).

-- economist Amartya Sen, WSJ.com

PS While we're on the topic of stealing from other blogs, let's have a word of the day: Froschmausekrieg

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Also in my mailbox

The new book Chaucer and Women (no copyright or publication data in English, other than EIHOSHA on the title page). It was sent to me from Japan by its author, Keiko Hamaguchi. Here is my favorite quote:

Here I must admit the surprising (to me, at least) realization that, were I transported via backwards reincarnation to Chaucer's London, I would likewise desire to be a silk hawking widow whom no one else bothers.

If I could travel back in time to Chaucer's England, What social position would I choose to occupy? I would choose to be a silkwoman in Chaucer's London. As an artisan, I would want to work as a silk weaver; or as a merchant, I would want to sell silk products. As to marital status, I would want to be a widow. Since I do not want to be bothered by anyone, I would prefer to work as a femme sole. After I explain why I would choose to be a silkwoman in Chaucer's London, I will explain why I would not choose to be a peasant woman, noblewoman or nun in the England of that time. (p. 118)

Here I must admit the surprising (to me, at least) realization that, were I transported via backwards reincarnation to Chaucer's London, I would likewise desire to be a silk hawking widow whom no one else bothers.

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Two letters from my departmental mailbox

(1) A typewritten missive that reads

[Enclosed is about 30pp of material, mainly typewritten. The pages are numerated, though they jump around (p. 65 is the first, p. 1216 the second ...) Many include illustrations of Lewis Carroll, sometimes with one fingernail hand colored with red ink.]

(2) A handwritten letter that reads

[Enclosed is a xerox of many typed pages about reincarnation, filled with statements like "Stalin was the reincarnation of Braxton Bragg, the Civil War general" and "The female prophet has been Madame Curie the scientist, Sarah wife of Abraham, and Cleopatra." All in all the writings amount to a full blown cosmology.]

Dear Professor Cohen

Responding to your appearance on "Quest for Dragons" (HISTORY CHANNEL, 28 Mar. 06), what could be more perfect than to introduce a NEW dragon of light through Algebra as applied to the English language?

Nonsense, you say? Right: Lewis Carroll's (see, ABSTRACT).

Please understand, the BBC has INSTRUCTED me not to write to them again. Oxford University refused (or destroyed?) my last letter, 30 years ago, for which I was paid $1.00. DISNEY, Inc., wanted all Rights-and-Title signed over to them, no purchase! Etc.

Thank you for your time.

[Enclosed is about 30pp of material, mainly typewritten. The pages are numerated, though they jump around (p. 65 is the first, p. 1216 the second ...) Many include illustrations of Lewis Carroll, sometimes with one fingernail hand colored with red ink.]

(2) A handwritten letter that reads

Dear Literature Professor

Included in this is startling, although possibly inaccurate, new information about Abe Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Babe Ruth, Gandhi, Stalin, Lenin, the Prophets, Madamme Curie, Eleanor Roosevelt and others. I am interested in your opinion. What I have written I am not sure should be published ... Here are copies of the pamphlets and leaflets I distributed soon after my last incarceration in a mental hospital. I distributed thousands of them on windshields and doorsteps.

[Enclosed is a xerox of many typed pages about reincarnation, filled with statements like "Stalin was the reincarnation of Braxton Bragg, the Civil War general" and "The female prophet has been Madame Curie the scientist, Sarah wife of Abraham, and Cleopatra." All in all the writings amount to a full blown cosmology.]

Tuesday, April 04, 2006

ye olde days of the internet

In the distant past of the early 1990s, technology was -- for the Average Professor or Pedagogue -- a wee bit frightening. TVs were OK, and computers that aided in word processing were fine, but the internet seemed like a place that sucked in your credit card numbers and otherwise abused your data. It was not, for the most part, a Scholarly Organ.

Medievalists, however, tended to be the exception. Because they love all things intricate, obscure, and difficult, they embraced the new world of email discussion lists, html and the WWW with gusto. And passion. Sometimes the flame wars on email lists like Ansaxnet were raging so heatedly that the dinky computers people possessed in those days of yore would combust. I know of one prominent medievalist who was badly singed and to this day refuses to keep his laptop on his lap.

In an attempt to place some order on this multiplying critical chaos, sorting sites like the Labyrinth at Georgetown were born. To encourage focus and depth -- and perhaps a bit more civility -- the electronic discussion group known as Interscripta was introduced. The first discussions were on Augustine and medieval subjectivity. Then, in 1994 (yes, I was alive back then -- a recent PhD in search of a tenure-track job) I moderated a colloquy on Medieval Masculinities. Medievalists from around the world participated. I then collated and shaped the ungainly thing into a hypertext article. Because electronic publishing meant little at the time (it was held in about the same regard as duplicating your work on a copy machine), I also arranged to have it appear in hard copy in the journal Arthuriana.

So why bring all of this up now? For a few reasons. Dr. Virago's recent query about men and feminism at Quod She. A graduate student conference that I attended at CUNY on "Masculinities in the Long Middle Ages" that proved to me the topic is still fecund. Discussions on several blogs about the identity work and experimentation that anonymous blogging enables. For me the Interscripta discussion -- held way back when a topic like masculinities was not yet part of the scholarly mainstream -- enabled me to pursue interests that were difficult to frame within the traditional graduate training I'd recently finished. I suppose this is just a long way of saying that the community which electronic communication fosters is, well, important -- and is often not deeply enough considered when we think about what shapes our scholarly lives.

Medievalists, however, tended to be the exception. Because they love all things intricate, obscure, and difficult, they embraced the new world of email discussion lists, html and the WWW with gusto. And passion. Sometimes the flame wars on email lists like Ansaxnet were raging so heatedly that the dinky computers people possessed in those days of yore would combust. I know of one prominent medievalist who was badly singed and to this day refuses to keep his laptop on his lap.

In an attempt to place some order on this multiplying critical chaos, sorting sites like the Labyrinth at Georgetown were born. To encourage focus and depth -- and perhaps a bit more civility -- the electronic discussion group known as Interscripta was introduced. The first discussions were on Augustine and medieval subjectivity. Then, in 1994 (yes, I was alive back then -- a recent PhD in search of a tenure-track job) I moderated a colloquy on Medieval Masculinities. Medievalists from around the world participated. I then collated and shaped the ungainly thing into a hypertext article. Because electronic publishing meant little at the time (it was held in about the same regard as duplicating your work on a copy machine), I also arranged to have it appear in hard copy in the journal Arthuriana.

So why bring all of this up now? For a few reasons. Dr. Virago's recent query about men and feminism at Quod She. A graduate student conference that I attended at CUNY on "Masculinities in the Long Middle Ages" that proved to me the topic is still fecund. Discussions on several blogs about the identity work and experimentation that anonymous blogging enables. For me the Interscripta discussion -- held way back when a topic like masculinities was not yet part of the scholarly mainstream -- enabled me to pursue interests that were difficult to frame within the traditional graduate training I'd recently finished. I suppose this is just a long way of saying that the community which electronic communication fosters is, well, important -- and is often not deeply enough considered when we think about what shapes our scholarly lives.

Monday, April 03, 2006

grad student blogs

Now that I'm closer to the end of the academic cursus honorum than its beginning, it's probably too easy for me to forget how difficult (emotionally, financially, institutionally) it is to survive the process in its earlier stages.

That's why I've enjoyed reading blogs like Ancrene Wiseass , Blogenspieland Heo Cwaeth so much. They are a constant reminder not only of what a struggle it can be for a bright person to run through the field's multiple hoops (grad school competition! qualifying exams! oral exams! a prospectus! a dissertation! the job market circus!) and break into the profession; they also give me much hope for what the future of the field will be like with people as smart and humane as this [hopefully] entering.

That's why I've enjoyed reading blogs like Ancrene Wiseass , Blogenspieland Heo Cwaeth so much. They are a constant reminder not only of what a struggle it can be for a bright person to run through the field's multiple hoops (grad school competition! qualifying exams! oral exams! a prospectus! a dissertation! the job market circus!) and break into the profession; they also give me much hope for what the future of the field will be like with people as smart and humane as this [hopefully] entering.

Paging Victor Frankenstein

JKW sends this link from the Economist, on a company that intends to manufacture heretofore mythical creatures from the DNA of lizards and other real animals: Here be dragons .

Didn't Michael Crichton write this story a long time ago?

My favorite lines from the article:

At any rate, I'm waiting for the kid's lab version.

Didn't Michael Crichton write this story a long time ago?

My favorite lines from the article:

Readers with long memories may recall GeneDupe's previous attempt to break into the pet market, the Real Goldfish. This animal was genetically engineered to deposit gold in its skin cells, for that truly million-dollar look. Unfortunately Dr Fril, a biologist, neglected to think about the physics involved. The fish, weighed down by one of the heaviest metals in existence, sank like a stone, as did the project.

At any rate, I'm waiting for the kid's lab version.

Gilles Deleuze

We know nothing about a body until we know what it can do, in other words, what its affects are, how they can or cannot enter into composition with other affects, with the affects of another body, either to destroy the body or to be destroyed by it, either to exchange actions and passions with it or to join with it in composing a more powerful body. (A Thousand Plateaus 257)

Gilles Deleuze has always been one of my favorite philosophers. Like Lucretius, Deluze was fascinated with the possibility that the worlds we inhabit might always be in motion, as dispersive and dispruptive as they are protean.

With Todd Ramlow I recently co-authored a short piece on Deleuze and queer theory. It was just published by the journal Rhizomes, and can be accessed here.

Saturday, April 01, 2006

It's kind of nice when Chaucer accurately Latinizes your name

and spells your honorific as professir.

This author is so clever that no good can come of it. Still, I will likely purchase a T shirt.

Prehistoric Ireland

Ireland was cold, wet, and wonderful. Though this was my third visit, it still seemed completely new.

The trip was -- for once -- not scholarly. At all. But because the Scholar Gene seldom goes dormant, I did take this wandering with my brother as an excuse to visit some of the sites that I've been thinking about. Lately I've been obsessed with prehistoric architectures, so I and my unwitting but patient companion explored a few of the famous ones like Newgrange and Poulnabrone dolmen -- both of which are really modern recreations of 5000 year old structures. I'll post more on that topic in the near future, and will also put up a syllabus for a course I taught last spring on "Fantasies of the Aboriginal" -- all about reading history as human story even when no textual record could linger.

Those interested in a selection of my non-scholarly, non-professional, and ultra-touristy photos may peruse some from a few of the places I passed through here. Warning: the captions and comments grow progressively sillier as the pictures advance. Second warning: you will lose all respect for me as a disembodied intellect when you see how quotidian and enthusiastic these reveal me to be.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)