Today's point of departure is the simple fact that all this talk about the sustained genetic purity of the Anglo-Saxons (were the aboriginal British wiped out so that a Germanic stock thrived in isolation?) can obscure the cultural hybridity that always erupts when one group welcomes, dominates, vilifies, eradicates, accepts, dreams about another.

A fuller discussion, less rough and with footnotes, can be found in Hybridity, Identity and Monstrosity in Medieval Britain. If I were to rewrite that chapter now, I would have emphasized more the violence that accompanies this moment of cultural contact; I fear that the discussion of hybridity comes across as too disembodied.

-----------------

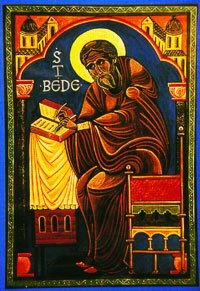

The Venerable Bede finished his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum [Ecclesiastical History of the English People] around 731. The heart of his narrative spans the fifth through early eighth centuries, a time when the isles were a maelstrom of cultural clash, admixture, alliance. The Picts and the Britons (disparate and shifting collectives of peoples, some Romanized, some not) formed their greater and smaller collectives, many enduring for years, others coalescing as briefly as the life of a warrior-king. Immigrants from Ireland arrived in what would someday be called Scotland and Wales, establishing the maritime kingdom of Dál Riata. Lively exchange with the continent was a constant. Beginning in the fifth century ethnically various peoples migrated from southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, assimilating or incorporating some indigenous groups, displacing or eradicating others. Over time these plunderers-turned-settlers combined warbands with more sedentary pursuits. Medieval writers referred to this settlement as the adventus Saxonum; modern historians label it the Anglo-Saxon migration, the foundation for what becomes England. Recent archeological and historical work has stressed the survival of native polities, forging out of patchy amalgamations of Anglo-Saxon and Romano-British elements emergent kingdoms like Mercia. Upstart realms fought relentlessly for hegemony, incorporating conquered rivals to form larger kingdoms, expanding into lands still held by Britons and Picts. These peoples, meanwhile, continued to form their own shifting solidarities, especially in the form of competitive principalities.

By the time Bede set pen to vellum the inhabitants of Britain had long spoken a variety of languages in an abundance of dialects. No doubt rapidly changing patois enabled trade and other less ephemeral forms of exchange. Many islanders would have been multilingual, indeed multiracial. The peoples of Britain were for much of this period more alike than different: possessing cultures and speaking tongues that lacked internal uniformity; prone to forming princely, kingly, and familial factions of variable scope and duration; mixing pastoral and pillage economies with less mobile religious and agrarian pursuits; willing to ally themselves militarily and matrimonially with those outside their linguistic and cultural circles. The British archipelago was, in short, as unsettled as it was compound, a dynamic expanse engendering what contemporary theorists of the postcolonial label creolization, métissage, doubleness, mestizaje, hybridity. No surprise, then, that "Anglo-Saxon England" is famous for its syncretism, its ability to embrace diverse and even contradictory traditions simultaneously.

Yet Bede stresses throughout his Ecclesiastical History the separateness and the supersession of insular peoples, a point emphasized even in his opening observation that Britain was "formerly known as Albion" (1.1; by whom he never says). He therefore acknowledges hybridity only obliquely. In the narrative arc formed by the Ecclesiastical History 2.13-3.3, we witness Edwin of Northumbria forsaking his native ways and converting to Christianity, reorienting his northern kingdom along a Mediterranean axis. The same king unites Britons and Angles in paninsular dominion. Rædwald of the East Angles, we are told, once erected a temple in which one altar served Christ and the other heathen deities. Papal epistles travel the world to ensure that the Northumbrian and Irish races (gentem Nordanhymbrorum, genti Scottorum) celebrate a unified Christianity. The pagan English of Mercia enthusiastically join forces with the Christian Britons of Gwynedd to overthrow Edwin. The exiled sons of Æthelfrith, the man from whom Edwin had captured the Bernician throne, dwell with their retinues among the Irish and Picts, awaiting Edwin's death. When these men return to their native kingdom, they immediately revert to their indigenous religion, a worship they had rejected after accepting baptism abroad. Oswald, the newest successor to Northumbria, is witnessed mediating the Irish tongue of the visiting bishop Aidan of Iona as he addresses the Angles:

It was indeed a beautiful sight when the bishop was preaching the gospel, to see the king acting as interpreter of the heavenly word for his ealdormen and thanes, for the bishop was not completely at home in the English tongue [Anglorum linguam perfecte non nouerat], while the king had gained a perfect knowledge of Irish [linguam Scottorum iam plene didicerat] during the long period of his exile. (Ecclesiastical History 3.3)

Bishop Aidan oversees monasteries that conjoin his native country to the Picts and the Angles. He lives on an island, Iona, which straddles the space between Britain and Ireland. His monastic community (if Adomnán of Iona is to be believed) amalgamates the Irish, Picts, English, and Britons. Through Aidan's friendship with Oswald, English Britain is transformed by Irish learning into a composite space (3.3).

Despite these multicultural vectors, however, most interminglings unfold only to be condemned. Rædwald's East Anglia is the location of the famous Sutton Hoo burial, an archeological discovery that – like the corpus of Old English poetry itself – suggests that the Rædwald's syncretism is far more indicative of the practice of Christianity in England than Bede's absolutist vision of pagan/Christian separation. Because Rædwald stations Christ alongside native gods and privileges neither, because his desire is to combine rather than to sort, the monarch must in Bede's account be deplored. The Mercians are allowed their alliance with the Britons only because they are pagans, and therefore as detestable as the confederates they treat as equals. The sons of Æthelfrith deserve their violent deaths because they move back and forth between the categories Christian and heathen, a troubling inconstancy rather than an easy fusion (they must be wholly one or the other; they are not permitted the strategic embrace of both). Oswald is allowed his Irish tongue and his subjects their Irish instruction because this source of Christianity does not come from a people, like the Britons, vying against Bede's Angles for possession of the island.

Onto Britain's primal and enduring heterogeneity Bede projects a reductive separateness. Bede's narrative is rather like the Hadrianic and Antonine walling projects that he describes early in the text, demarcations that engender unity through exclusion. In Bede's vision the entirety of the island constituted the natural dominion of a singular gens Anglorum, the English people. This group did not quite exist in Bede's day. Yet by imagining the island's past as a story heroically accomplished by this putative collective, by distilling a complicated historical field into the chronicle of a single people, Bede breathed life into the collective identity English and aided in the genesis of what was to become Europe's most precocious nation. The Ecclesiastical History imagines a past that, despite ample evidence to the contrary, seems monolithic, pure.

No comments:

Post a Comment