Wednesday, June 25, 2014

SNEAK PEEK: Preview of Materiality Sessions at #Kzoo2015

Hey medievalists! You can now take a sneak peek of approved sessions for #Kzoo2015 (i.e., the 50th International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, MI, May 14-17, 2015). The sneak preview information is on this page; you can also directly view the sneak preview of sessions as a PDF.

One idea that emerged through some private discussions on Facebook was to think creatively about more dynamic and deliberate "cross-fertilization" across disciplines and subfields. Some of my Facebook friends picked up on a real interest in materiality at the 2014 conference. Through such virtual correspondence it has been noticed (for instance) that musicologists and literary scholars don't actually interact with each other as much as they could (should!) about the intertwined materiality of sound, text, and notation -- so it would be great to put our heads together to think about things like aurality, language, embodied performance, etc. In what other ways can we all move out of our various bailiwicks and "mix things up" in our sessions?

Here's a list of materiality-related sessions for #Kzoo2015. Full contact info is on this PDF.

It's a great slate of sessions. Think creatively! Consider sending in a proposal to a session that is outside your (sub)field or discipline or otherwise allows you to interact with new people! Perhaps a compelling (unofficial) "Materiality" thread can emerge from the conversations that transpire.

Sessions with materiality in title:

Association for Spanish and Portuguese Historical Studies (2): Material Iberia I: Devotional Objects, Devoted Bodies; Material Iberia II: Shaping Bodies in Literature and Art

Friends of the Saints (1): Material Engagements with the Friends of God in Post-Roman Europe (panel discussion)

Magistra (1): Mysticism and Materiality (panel)

Material Collective (1): Transgressive Materialities

Medieval Romance Society (3): Romance Materiality I–III: The (Im)materiality of the Book; Romancing the Material; The Material Afterlife

Mid-America Medieval Association [MAMA] (1): Economic and Material Collectivity and Exchange

Musicology at Kalamazoo (1): The Materiality of Music (panel)

postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies (1): Quantum Medievalisms (roundtable)

Societas Magica (1): Magic and Materiality

Society for Medieval Feminist Scholarship [SMFS] (1): Gender and Materiality in the Middle Ages

Society for the Study of Disability in the Middle Ages [SSDMA] (1): Disability and Material Cultures (roundtable)

Special Session: (Im)Materiality in English and Welsh Medieval Culture (1)

Special Session: When Objects Object: Misbehaving Materiality (1)

Sessions otherwise interested in materiality:

George Washington University Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute [GW MEMSI] (1): "Lost" (panel)

Grammar Rabble (1): Unsettled Marks: To #;()@?”:-*! . . . and Beyond! (roundtable)

Friday, June 20, 2014

Ice at #NCS14

|

| Langjökull, which I hiked with my family in 2012 |

The most recent International Congress on Medieval Studies at Kalamazoo was wonderful in many ways, but also at times reaffirmed my increasing dissatisfaction with traditional conference panels. Three or four loosely connected papers plus a response and then (if there is time, because inevitably someone has gone too long) aleatory questions from the audience that may advance the communal topic or may (if the session chair is not moderating) allow the three people who study liturgy to render the session on postcolonial medieval studies a liturgy session because one paper had a brief reference to liturgical calendars -- well, I don't always get as much as I would like from such gatherings. Blogs and other social media have made these loose sessions less useful than they were in the past, since it is now fairly easy to garner public feedback on ideas and projects without reading an excerpt in front of an audience for fifteen minutes. Such sessions can be productive, especially when the theme is specific, the papers carefully curated by the organizer, and the panel moderated so that the conversation is inclusive and focused. But that does not always happen. I find myself drawn more to sessions with multiple, short presentations and lingering discussion afterwards, to roundtables that approach a single issue from multiple perspectives, and to spaces adjacent to as well as within the conference that are not part of the official program.

I've written here at ITM about para-conference space as a fecund expanse for modes of thinking and doing that official conference sessions disinhibit: see the justification for the GWMEMSI Rogue Session at the last Kalamazoo, as well as my account of what actually unfolded there. For the upcoming BABEL conference in Santa Barbara, a large group of us (13!) crowdsourced and brainstormed a special session on SCALE that includes an outdoor "collaboratory" in the Channel Islands. The day before the conference begins, we will take a boat to Santa Cruz and hike the rocky canyon around Scorpion Bay, hoping something will emerge from this peripatetic and communal cognition that would not have been possible within a conference room. And at the upcoming New Chaucer Society Biennial Congress in Reykjavik, I've arranged two roundtables on "Ice" that will include a group hike of Sólheimajökull, a glacier in the south of the island. If time permits we will also head to Eyjafjallajökull, the ice topped caldera of a nearby extinct volcano. Oddur Sigurðsson of the Icelandic Meteorological Office (and respondent to the Ice roundtables) will lead us, since he knows this glacier intimately through his studies. We've hired a well reputed expedition company to supply us with the necessary equipment and keep us safe. It seems to me that if we are going to gather in Iceland to speak about representations of ice, if we are going to theorize ice and think with it, we also ought to walk across a frozen expanse together.

If you are attending NCS, I hope you'll come to the roundtables on the first day of the conference. Abstracts for the presentations are below.

Wednesday, June 18, 2014

JJC on Van Helsing

Karl has been filling the blog with Deep Thoughts: see here, here, here and here for some substantial fodder for your own rumination.

Meanwhile, if you are interested in something lighter for summer delectation ... here is a short video from the production blog of the Showtime series Penny Dreadful, in which I speak about Professor Abraham Van Helsing. Oddly enough John Logan mentioned Monster Theory in the pitch he made to the cable channel to fund the series, so I will be back when season two begins to speak about that book.

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Two points: Digital Piers; Marsilius of Padua and the problem of "agency"

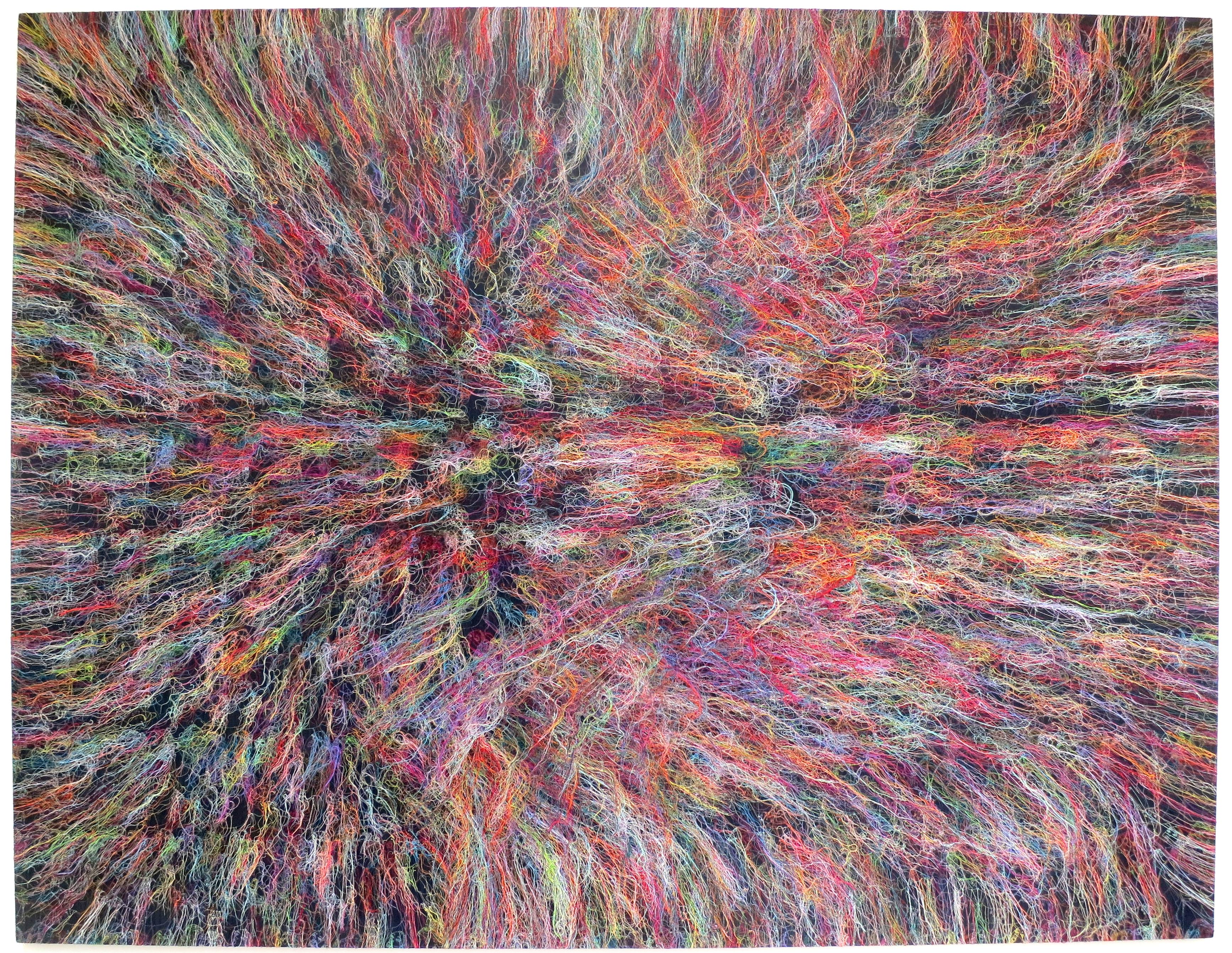

|

| Ghada Amer at Cheim + Read |

Two quick points:

ONE. First, if you're a medievalist, particularly a digital humanities medievalist, and you're not reading Angie Bennett Segler's Material Piers blog, you're making a terrible mistake.

Piers Plowman doesn't get a lot of love around these parts. I'm not sure any of us here have ever taught it. For that reason, alone, you should be reading Material Piers. You know, to expiate our guilt. Or at least my guilt.

Here's a sample:

At present, it’s relatively established that the Vernon [manuscript] cannot possibly be dated to prior to 1395. Good, fine. No problem. That’s the fourteenth century. BUT, and for me this is a big “but,” the Vernon is SO MASSIVE that it seems pretty much insane to me to date it to any year. The majority of the manuscript, along with its almost as large sister the Simeon, was copied by a single scribe!! A.I. Doyle estimates that even moving at his fastest he couldn’t have completed the pair of them in under FOUR YEARS, and it may well have taken up to eight. On top of that, there is the lavish decoration scheme with borders, initials, gilding and two full cycles of miniatures. The idea that the manuscript was both started and completed in the fourteenth century borders on preposterous.

That, frankly, is why I prefer dating V to “ca. 1400.” Because the “circa” itself implies a possible range of time. And in the case of the Vernon, that range is incredibly important. But more than that, it acknowledges the imprecision in dating manuscripts altogether. “Ca. 1400″ allows us to think about the slipperiness of dating things belonging that far in the past and about the time it takes to hand-make a material-textual object, to bring it into being one folio, one line, one letter, one stroke at a time. So, unless a manuscript is clearly and definitively datable to a certain decade, I prefer to leave it with its ambiguous date.And here's a chart. which you can understand if you click through to the blog!

Why am I demanding that you read this Material Piers post in particular? Because it offers you the chance to do a bit of digital humanities work yourself. Read the post; lend a hand; and join me in swimming in a Piers-and-everything-else manuscript. I'll be doing that myself this afternoon.

TWO. The various so-called "new" materialisms tend to use the word "agency" a lot without doing much to figure out what the word actually means. My second Kalamazoo2014 paper, on spontaneous generation and "automatic" agency, tried to get directly at the problem by arguing, ultimately, that only a random break with mechanical causality can be recognized as truly agential. My solution has the posthuman advantage of moving questions of agency away from rationality and anthropomorphism, thereby avoiding the implicit humanizing at the center of many discussions of agency. It also has the dubious -- and predictable -- advantage of discovering an aporia at the agency's heart.

All this is by way of setting up a passage from Marsilius of Padua's Defensor Pacis:

This term "ownership" is used to refer to the human will or freedom in itself with its organic executive or motive power unimpeded. For it is through these that we are capable of certain acts and their opposites. It is for this reason too that man alone among the animals is said to have ownership or control of his acts; this control belongs to him by nature, it is not acquired through an act of will or choice. (II.12.16, p. 193)

Adhuc dicitur nomen dominii de humana voluntate seu libertate secundum se, cum ipsius executiva seu motiva organica potestate non impedita. Hiis enim possumus in actus aliquos et ipsorum oppositos. Propter quod eciam dicitur homo inter animalium cetera suorum actuum habere dominium; quod siquidem a natura inest homini, non voluntarie seu eleccione quesitum. (MGH 271)The origin of human agency ("ownership of control of his acts") isn't human agency itself. Rather, it's inherent to humans, unchosen. Agency itself therefore is free from human choice at its root. Still, it's determined, somehow, by "nature." If the power of choice is instinctual, then it's hard to imagine that humans have "complete freedom" ("libertas," I think). This problem of the origin of agency is a problem, especially, for Marsilius, as he's well-known for arguing that "the supreme power resides in the body of the citizens [and not the Church], who make the laws, and choose the form of government, etc [and that t]he prince rules by the authority of the whole body of citizens": what is the origin of the people's will?

But the problem is also general to agency and to human agency especially, perhaps the paragon and model of agency in any discussion of the term. The problem of agency intersects with a host of other problems, of materialism, humanism, racism, and indeed the history of antisemitism.1 It's a problem whether we're talking about rats or stones or garbage or the tedious Pauline differentiation between Christian spiritual reading and Jewish literal reading or, for that matter, the whole spirit versus matter binary that's inherent to all considerations of agency. For any of these, the power of agency simply doesn't seem to be reducible to any first cause. Otherwise, it wouldn't be agency but rather the beginning of another mechanical chain.

In short, any clear claim to agency strikes me as unwarranted. And the same goes for any scorn of materialisms or posthumanisms because their "discovery" of agency in nonhuman objects.

It's obviously ironic that I should end up so automatically in an identifiably deconstructive aporia. I'm very much back in Derrida's critique of the "auto" of autobiography in, for example, The Animal that Therefore I am, where he does his Derridean thing with the "ipseity, indeed sui-referential egoity, auto-affection and automotion, autokinesis, [and] autonomy" (65) of the presumptive presence of the self-generated automatic I, and with the pretense of "auto-motricity, a spontaneity that is capable of movement, of organizing itself and affecting itself, marking, tracing, and affecting itself with traces of its self" (49). You can imagine what happens to agency when Derrida finishes with it.

Maybe commentators can suggest another way forward?

1 Or, for that matter, colonialism and its various justifications. See this new post from Corey Robin, on the dangers of presidential boredom, where he recalls Tocqueville's enthusiasm for the Opium War: "So at last the mobility of Europe has come to grips with Chinese immobility!" ↩

Monday, June 16, 2014

Sovereignty, Biopolitics, the Forest, and the King's Jews: Sketch for a Research Program

|

| Tony Lewis from Whitney Biennial |

What the title says. Over the past couple days, I've been reading David Nirenberg's forthcoming Neighboring Faiths: Christianity, Islam, and Judaism in the Middle Ages and Today, whose fourth chapter makes an old point with atypical neatness:

Medieval kings had expanded their sovereignty (in part) by assigning the Jews to a status outside normative law and claiming exceptional power to decide their fate. Sovereign power was thus (in part) performed through the protection of those who had denied God's sovereignty, his 'enemies' and 'killers.'Nirenberg argues that kings would later demonstrate their sovereign power not by protecting but by murdering and expelling Jews: the sovereign exception, as we know, can go both ways, towards "mercy" or towards the full, arbitrary exercise of the Law, nothing at its core but the king's whimsy. If not in practice, at least in sovereign fantasy.

Nirenberg brilliantly connects this medieval sovereignty to famous passages in Schmitt and Benjamin ("Sovereign is he who decides the exception" and "The Prince, upon whom the decision over the exception rests, discovers in the best of situations that a decision is impossible for him") and from thence to the "miracle" in Schmitt and Benjamin, and, as expected, to the redemptive rereading of the political miracle in Agamben, Žižek, and Santner. Almost needless to say, Nirenberg isn't on board with the miracle in any form, neither in Schmitt's sovereign version nor the post-Sovereign versions of B, A, Ž, and S.

More about that much later (like, later this year). What strikes me now is the relation of Nirenberg's point to one I'm making in an article, "Biopolitics in the Forest," that will appear in Randy Schiff and Joey Taylor's Politics of Ecology anthology. You've had the chance, often, to see preliminary bits: here, here, here, and here (and even this post from 2006). The article's key argument is that the sovereign exception and biopolitics each sprang up simultaneously in the 12th-century English forest. Biopolitics is not a paradigmatic modern form of governmentality that follows long after sovereignity, but rather coincides with sovereign claims; also coincident with those claims is the way that bodies "naturally" resist biopolitics, a point I'm developing from Cary Wolfe. As Wolfe argues, and me with him, agency and objecthood, the problem of the possibility of "conscious resistance," and other humanist, rationalist concerns start to fall away once we start to think about bodily forces in biopolitics. Thinking like that makes way for thinking about animals in the political community, Wolfe's main point, but it also makes room for thinking more fluidly about dominated humans. Like, for example, the Jews of thirteenth-century England.

Here's how it goes in the article itself:

Husbandry is the scandalous foundation of a biopolitical analysis that has tended to be committed, more or less explicitly, to defending human particularity by trying to keep humans from being treated “like animals.” Foucault observes that “Unlike discipline, which is addressed to bodies, the new nondisciplinary power [of biopolitics] is applied not to man-as-body but to the living man, to man-as-living-being; ultimately, if you like, to man-as-species” and that in sixteenth and seventeenth centuries we witness the “development of a medicine whose main function will not be public hygiene, with institutions to coordinate medical care, centralize power, and normalize knowledge.” Esposito writes that in modern biopolitics “life enters into power relations not only on the side of its critical thresholds or its pathological exceptions, but in all its extension, articulation, and duration,” and calls this a “new rationality centered on the question of life.” The obvious modernist and humanist biases of these observations ought to be contested. When Foucault states that “man is to population what the subject of right was to the sovereign,” or Esposito explains that biopolitics aims not only at “obedience but also at the welfare of the governed,” their analysis might have gone even further had they said that biopolitics treats humans like livestock, or, more particularly, like the sovereign’s livestock, which is to say, like venison.I stand by that argument. But Nirenberg reminds me of something that I missed, which is another 12th/13th-century English (for example) development of both sovereignty and biopolitics. The king called the Jews his Jews, and (so?) they were the victims when the King's subjects rebelled (for example, in the 1260s, against Henry III, and also especially in York in 1190, committed when Richard I was--as was his habit--overseas). Also note this antisemitic 13th-century cartoon, where Isaac of Norwich is represented wearing Henry III's crown (and read the post itself, while avoiding its comments). That's sovereignty, and a set of standard resistances to sovereignty.1

But there's also biopolitics. Strikingly, a lot of regulation about the Jews in England, first from the church and then from the crown, tries to manage what might be called biological relations between Christians and Jews. The 1219 statutes of William of Blois, Bishop of Worchester, for example, forbid Christians from serving Jews as nurses (see also here). Other statutes, echoing Lateran IV.68, explain that Jews should wear a badge to prevent sexual mixing between Christians and Jews [the same statutes, better edited here, 121, have "quoniam in partibus istis sic inter christianos et iudeos confusio inolevit ut fere nulla differentia discernatur, propter quod nonunquam continigit quod christiani iudeis mulieribus commiscentur"]. That's the church. But then January 1253 Statute of the Jews gives a secular reaffirmation of these and other points. In regards to the Jews, English sovereignty and biopower had now combined.2

Putting aside the question of whether the conciliar decrees were enforced, and the related point of whether the laws were simply mechanical repetitions of older laws (like these or these), we might observe that the laws themselves witness to the fact that bodies are a place for sovereignty to expand its area of concern. Bodies must be managed, not just by violence, but also by nurturing, to maintain the health of populations and to prevent contagion. Bland points like these of course take on a sinister aspect when we remember that we're talking about relations between a dominant Christian majority and a dependent Jewish minority. We know that concern for the health of the body politic or the corpus christianorum could just as well be murderous to those marked as not belonging. It might even turn against members of the community, accused, for example, of "judaizing." That's the model of biopolitics as the extension of sovereignty, and it's what we find especially in Roberto Esposito.

Simple points like these will reshape my considerations of sovereignty and biopolitics in 12th and 13th-century England. The baronial killing of Jews is analogous, mutatis mutandis (!), to poaching the king's deer: that's resistance to sovereignty. The insistence that Christians not eat food rejected by Jews, and that Jews not nurse Christian children and vice versa may be analogous to the necessity of royal management of cervid populations in hunting preserves. That's biopolitics.

And, as with the cervids, we'll probably find that bodies, even under sovereign control, act independently. Here's Cary Wolfe, from Before the Law:

the power of Foucault's analysis is to demonsrate just how unstable and mobile the lines are between political subject and political object--indeed to demonstrate how that entire vocabulary must give way to a new, more nuanced reconceptualization of political effectivity. And equally important is that Foucault's introduction of "life into history"--of the body in the broadest sense of the political equation--does not lead directly and always already to an abjection for which the most predictable tropes of animalization become the vehicle.Bodies will do what they have to do. This isn't a matter of agency, nor a matter of complete exposure, nor a matter simply of suffering or of being "reduced" to animal, bare life. This isn't the lachrymose biopolitics of Agamben and Esposito, whose only escape is some kind of messianic break. Rather, this is an array of forces, in which subjects do suffer but in which they also inevitably resist, regardless of whether they want to or not.

We know Jews and Christians mixed in medieval England (for example). They probably did eat and drink together from time to time, again, just because a body, infant or adult, has to eat. Since that bodily need can't be stopped, since it will find its own solutions, independent of biopolitical control, things will inevitably go awry. Note this: thirteenth-century English laws that compelled Christians to refuse meat that the Jews had themselves rejected ended up requiring Christians, in effect, to keep kosher, and this during some of the worst persecutions of Jews in England's history. The imperative, then, is to follow up on points like these to find moments where bodily control in an antisemitic biopolitical regime behaved, well, oddly, to trouble our sedimented, humanist notions of agency, political control, and "active" rebellion.

One last irony, as a repulsive epilogue: the ritual murder charge -- dating from the mid 12th century and probably originating with an English monk -- often accused Jews of anthropophagy. The Jews, supposed to want to kidnap and torment Christian children to enact their contempt for Christ, were often supposed to want to eat them too. See especially the "Adam of Bristol" story, where Samuel, the murder’s chief architect, promises, “I will rotate him” so that “this body of the God of the Christians will be roasted by the fire just like a fat chicken" [“ego regirabo”; “assabitur corpus dei christianorum, iuxta ignem sicut gallina crassa"].3

Now, of course, this charge could not be a more obvious example of psychoanalytic projection, since the Christians were the "real" anthropophages; they, not the Jews, ate their god.

And sometimes Christians ate their own martyrs. In the late eighteenth century, Dean Kaye and Sir Joseph Banks opened the tomb of young Hugh of Lincoln, murdered by Jews, as the (false!) story goes, stuffed in a well, and then retrieved to be buried as a martyr. Inside the tomb, they found a child's body wrapped "in a leaden cere cloth, in a kind of pickle (which Sir Joseph is said to have tasted), but whether so perfect as to show the marks of crucifixion we are not told."

Which Sir Joseph is said to have tasted. Bodies go awry.

Meanwhile, during the period of Hugh's supposed murder, the English Christians were, in fact, dumping the bodies of Jews, including children, in wells, no doubt poisoning their own drinking water. And so the rebellion against sovereignty leads us, also, to biopolitical failure.

1 Robert C. Stacey “Anti-Semitism and the Medieval English State,” in J. R. Maddicott and D. M. Palliser, eds, The Medieval State: Essays Presented to James Campbell (London, 2000): 171-72 [163-77]↩

2 John Edwards, “The Church and the Jews in Medieval England,” in The Jews in Medieval Britain, ed. Patricia Skinner (Boydell & Brewer, 2003), 91 [85-96]; See also J. A. Watt, “The English Episcopate, the State and the Jews: the Evidence of the Thirteenth-Century Conciliar Decrees,” in Thirteenth Century England II. ed. P. R. Coss and S. D. Lloyd. Proceedings of the Newcastle Upon Tyne Conference 1987. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell P, 1988, 137-147↩

3 Christoph Cluse, "‘Fabula Ineptissima’: Die Ritualmordlegende um Adam von Bristol nach der Handschrift London, British Library, Harley 957" Aschkenas 5 (1995): 293-330↩

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

THE HORDE (2012): before before Orientalism, the new (?) medievalism

|

| Nuts, Turnips, Water, Blood, Bread, Watermelon |

|

| click to ENLARGE |

1 Noreen Giffney has written well both on the need for an engagement with the Mongols informed by theory (see here, especially) and, here, on how discourses of monstrosity and apocalypticism play out with thirteenth-century Christian depictions of the Mongols, particularly with Matthew Paris, Thomas of Spalato, The Chronicle of Novgorod, and Ivo of Narbonnes. Thanks to Michael O'Rourke for the reminder. And for a far more detailed and expert engagement with the Mongols than I can provide, listen to 2013 UCLA Conference on "The Mongols from the Margins: New Perspectives on Central Asians in World History," particularly Christopher Halperin's "No One Knew Who They Were: Russian Interaction with the Mongols." Thanks to Sharon Kinoshita for alerting me to the conference records.↩